Great news! My collaborator Stacy Williams-Duncan and I have a new article out in the interdisciplinary Journal of Media Literacy Education! It’s called “Faith Leaders Developing Digital Literacies: Demands and Resources across Career Stages According to Theological Educators.”

The article was inspired by the call for papers for this special issue on media literacy education for all ages.

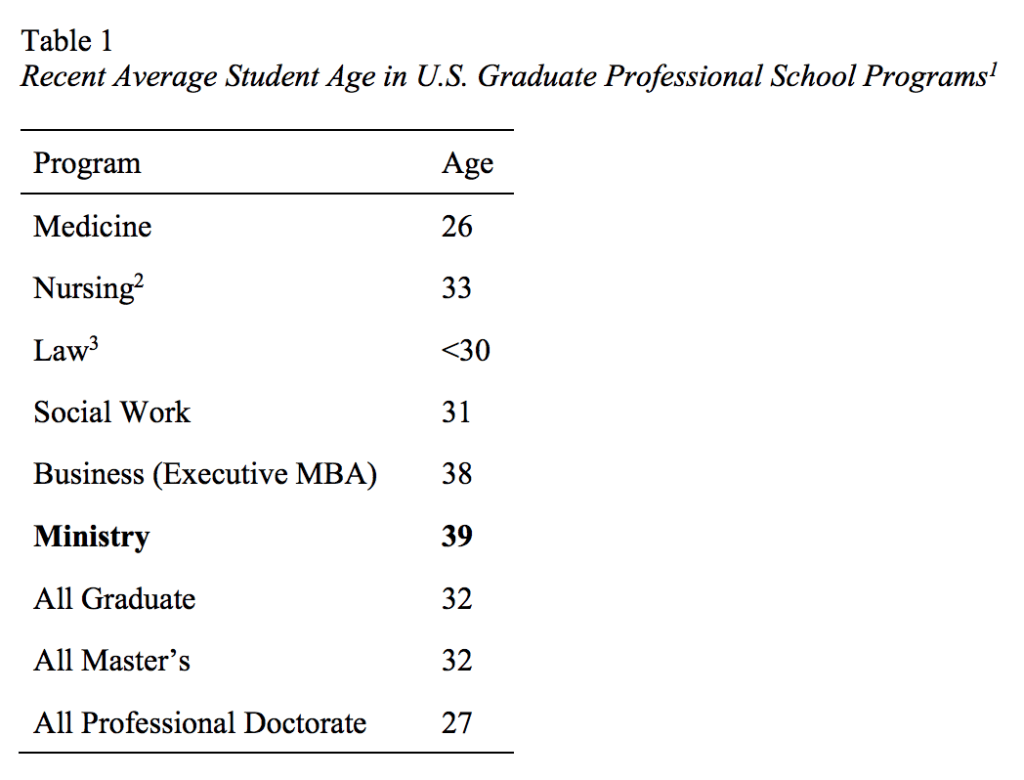

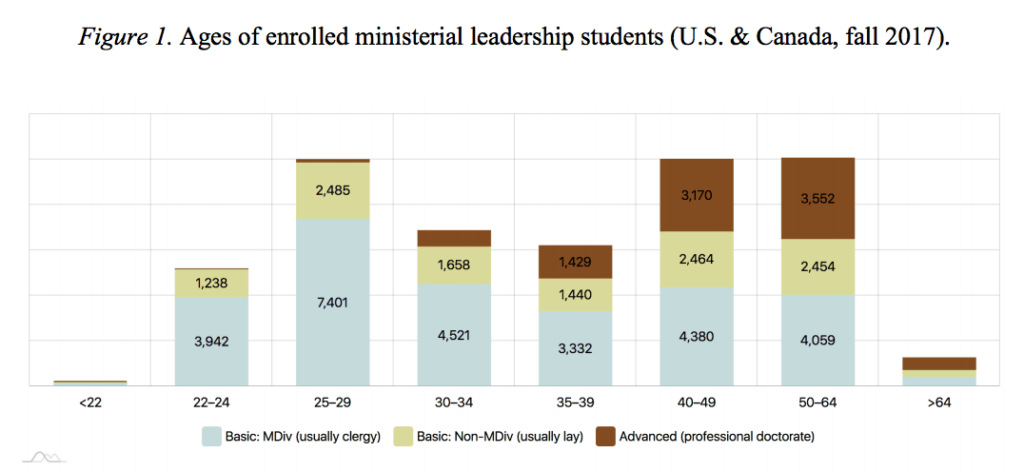

Theological education is an especially rich context in which to investigate this topic, because the age range of students preparing for religious leadership is unusually broad compared to the student bodies in other, mostly much younger fields of professional study:

The backstory here is that while we were working to find the right home for the “foundations paper” about our first-of-its-kind study of digital literacy instruction in theological education (we’re revising that manuscript in light of reviewer comments as I write this), this special issue came along and inspired a re-analysis of our data with special attention to what participants told us about the ages and career stages of their students and what, if any, patterns they noticed about the kinds of tasks students excelled in or struggled with.

For me, the exciting takeaway of the piece is the way it challenges us to think more critically about who’s “good at” (or not) using new media in ministry. Our findings suggest it’s complicated and nuanced.

Yes, there are skills many younger students seem to to excel in and older students tend to struggle with, as the popular imagination might suggest. But the opposite is also true. There seem to be skills for which older students’ personal and professional experience effectively prepares them (think later-in-life “funds of knowledge“), skills that younger students are more likely to struggle with.

That this is the case in general won’t be a surprise to theological educators. But as developing digital literacies becomes a more important part of the explicit curriculum in theological education, we agree with one study participant “that instructors need to ‘complexify’ their understanding of … early-career students and ‘not to romanticize that they [always] understand what they’re doing [online]” (p. 138). The same goes for the tired and false assumption that older students generally don’t.

Of course, we’re still chewing on some of what this might mean:

as this article has occasioned our re-immersion in colleagues’ reflections on their teaching practice, we have become increasingly intrigued by the question of what it means for adult practitioners in any field to be socialized into online communities popularly understood as youth- and young adult-oriented or -dominated. As reported above, many of the transcript excerpts Oliver originally coded as age-related focused on learning to reach a younger audience online. To the extent that this framing is accurate, it raises the question of how mid- and late-career professionals participate authentically in digital cultures. And since we know the youth-oriented framing is reductive, it also raises the trickier question of how older students—and the older educators teaching in professional schools—can claim the DLM insight and authority their experiences have given them.

(p. 140–141)

(It would be gross professional negligence at this point for me to fail to mention #hotpriestsummer as a wonderful example of these tensions and overturned stereotypes in action.)

JMLE is open access, so you can read the article for free—forever, unlike my piece in Teaching Theology & Religion, which goes behind a pay wall next year.

Have a look and let us know what you think!

And if you’re dying to know more about the research that this particular analysis revisits as we wait on peer review, you can check out the original poster or this summary over on the website we built to help support the teaching of the literacies our research participants identified.

Photo by NEC Corporation of America, via Flickr (CC BY 2.0).