The Feast of Sts. Peter and Paul

(Ezekiel 34:11-16; Psalm 87; 2 Timothy 4:1-8; John 21:15-19 )

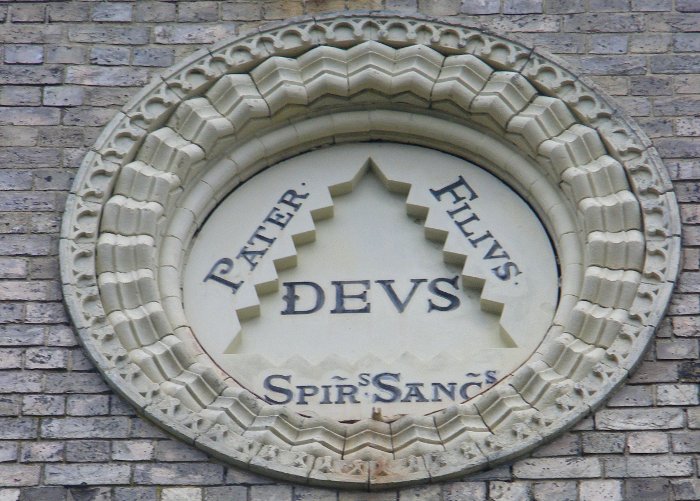

Image source: Wally Gobetz via Flickr

PDF | Audio (or via Dropbox) | Text:

“It takes all kinds,” my mothers says from time to time. To be a family. To be a team. To be the Church. It takes all kinds.

My mom should know. Her ministry in two very different parishes has always emphasized the full spectrum of their diversity. She taught me that it takes all kinds of people to be the Body of Christ as she participated in ministries with preschoolers, middle schoolers, the sick and elderly, and the homeless and urban poor. And she taught me that it takes all kinds of viewpoints to keep a church moving forward in healthy ways. In a time of deep division and conflict in their parish, I watched both my parents hang in there through the pain and strife and to help with the healing when the congregation turned a corner. The faithful message I heard from them throughout the ordeal was that we can’t let disagreement be a barrier to belonging. I’ll probably always think of that time and their quiet witness when I hear these words from 2 Timothy: “be persistent[,] whether the time is favorable or unfavorable” (4:2).

“It takes all kinds” may well be the principal message of our half-patronal feast today. Sure, Sts. Peter and Paul have good reason to claim the top spots in the ecclesiastical power rankings and to share a big summer celebration. But part of what makes today poignant is the study in contrast these two provide. Cue the orchestra, it’s time for the sermon equivalent of “Let’s Call the Whole Thing Off.” I’ll spare you my Louis Armstrong and Ella Fitzgerald impressions.

Peter, it seems to me, says po-tay-to. He’s a bit of a jock, has the rugged outdoorsman thing going. He doesn’t think twice about jumping in the water—fully clothed—to swim to his Lord on the shore. He’s a little more set in his ways, as rural residents tend to be; it took some convincing on God’s part for Peter to warm up to the idea that “What God has made clean, you must not call profane” (Acts 10:15). But Peter can also be perceptive—or is it impulsive? Either way, he’s the first of the disciples to confess Jesus as the Messiah.

Paul, on the other hand, says po-tah-to. He’s cosmopolitan, an urbanite, more of a bookworm, weak in body—and content with his weakness. He has a city-slicker’s tidy understanding of nature, lacking the sense of wildness we get from the imagery in, say, Mark’s gospel. And if you’ve ever gotten tired of the phrase “by no means,” then you know Paul is someone who knows how to “think slow” and carefully work through a complex argument.

So it takes all kinds not just to be the church, as my parents showed me, but to build the Church, as today’s saints helped do despite differences and even chafing between them. We could go on all day about the differences between Peter and Paul. But there’s more to this feast than ee-ther and aye-ther. A look at their similarities ought to bring us up short too, ought to remind us that we need each other not just because we complement each other but because we need all the help we can get on a journey that will beat us up along the way. It’s no surprise that as we celebrate the lives of two early Christian martyrs, we hear readings that understand the cost of their apostleship.

From John’s resurrected Jesus, Peter gets some sobering words in today’s gospel passage: “‘Very truly, I tell you, when you were younger, you used to fasten your own belt and to go wherever you wished. But when you grow old, you will stretch out your hands, and someone else will fasten a belt around you and take you where you do not wish to go.’ (He said this to indicate the kind of death by which he would glorify God.)” (John 21:18) [Pause] And from the Epistle, our patron saint speaks for himself: “As for me, I am already being poured out as a libation, and the time of my departure has come” (2 Timothy 4:6). There’s a gracefully accepted road-weariness alongside the celebration in these readings. The Christian life is like that, isn’t it?

So it takes all kinds of companions on the journey. Companions who see the obstacles in our path just a bit differently from how we do, perhaps even seeing them as blessings. Companions who remind us that we ourselves are no picnic some of the time. Companions who love us anyway, and need our love too.

Two things happened on that walk of faith this week, within a couple hours of each other on Wednesday morning. The first was the Supreme Court’s decision that the Defense of Marriage Act had served “to disparage and to injure those whom the state, by its marriage laws, sought to protect in personhood and dignity” and that the law was therefore unconstitutional. The second was the announcement that Fr. Humphrey has accepted a call to help lead the Church of St. John the Evangelist in Newport, RI in the next stage of their life together. To be honest, I didn’t know which lead to bury.

Regarding the former, suffice it to say that the Supreme Court Decision was a source of great and long-awaited rejoicing for many, including many in this parish. It was also an unwelcome source of trepidation and disappointment to plenty of others, including some in this church and many in the wider Church. It’s not the last decision that our legal jurisdictions will have to make about same-sex marriage, and our theological conversations in the church catholic, the Episcopal Church, and St. Paul’s Parish will all continue for years to come.

It happens to be my opinion, by which I mean my own opinion and not an official position of this church or its clergy,* that it takes all kinds of marriages, including same-sex marriages, to testify that “all [persons] are created equal” and to signify “the mystery of the union between Christ and his Church” (Book of Common Prayer, 423). But I believe it’s a fact that no court, no country, and no church can function in a healthy way without a willingness to talk honestly and lovingly about disagreement and to resist the urge to declare the other, any other, to be beyond the pale. St. Paul’s Parish, and Anglican Christianity on the whole, has a long tradition of being a safe place for as wide a cross-section of people as wish to be here. I pray that that God will continue to show us the way to live faithfully into this vocation.

Regarding Fr. Humphrey’s departure, there will be opportunities to say thank-you and goodbye in the coming weeks, but let me for now share this one story. Last spring, Fr. Humphrey wrote to me and said “You’re about to learn that life is a series of transitions.” These transitions are not always easy, but they are always an opportunity. An opportunity to give thanks for what God has done for us, and to wait in hopeful expectation for the blessings that will surely continue to flow by the Spirit. If it seems like we’re confronting more than the usual share of transitions around here lately, I hope we can also remember the great privilege of our years of fruitful ministry with Fr. Humphrey, with Deacon Eric, with Melva Willis, and with Josh Stafford, and to be grateful for their presence among us a bit longer.

Phew. A lot happened on Wednesday, and in the last few months. And a lot will happen as we continue on. The times will be favorable and unfavorable. Especially amid continued transition and change, it will take all kinds to be the human family, to be the Church, and to be St. Paul’s K Street. It will take all kinds because the Father has created all kinds. It will take all kinds because the Spirit has sanctified all kinds. It will take all kinds because Christ will draw all kinds unto himself.

Our task as disciples, as “heirs through hope” of the Kingdom and of the Church Peter and Paul helped build together, is to place ourselves on the foundation of Christ’s love. And on the days when we’re feeling that road-weariness the saints know all too well, we can turn in our weakness to these words from, of all people, the prophet Ezekiel: “I myself will be the shepherd of my sheep, and I will make them lie down, says the Lord GOD. I will seek the lost, and I will bring back the strayed, and I will bind up the injured, and I will strengthen the weak.”

Believe it, my sisters and brothers. Believe it.

*Preacher’s note: I gladly added the italicized clarification at the 11:15 service at the instruction of the Priest in Charge.