Before there was Becoming Tapestry there was … something else.

I had planned on calling the series Faith Adjacent (read idea refresher here) in order to more squarely associate my dissertation podcast as a whole with one of the core intellectual contributions of the project.

My tentative plan was to produce a more mixed-genre series that would continue season by season in a robust way after I had defended. Short documentary episodes exploring my research, across both the pilot and the main study, would be interspersed with colleague chats (see Bonus 2) and possibly with case studies from other faith-adjacent communities. Think less of an account, more of a platform.

Making the familiar …

The third bonus episode of Becoming Tapestry is the pilot episode for that now-abandoned series.

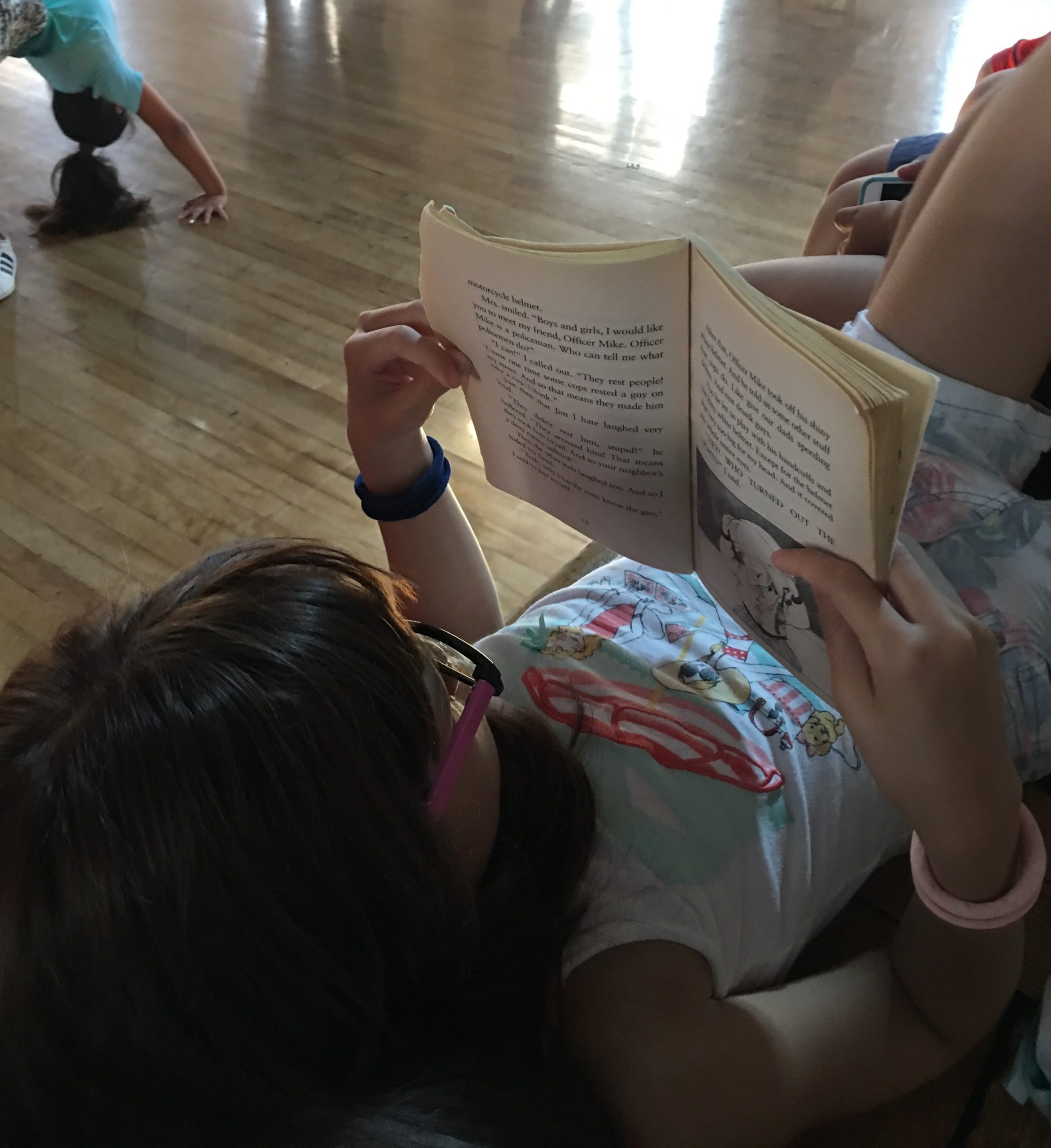

So there’s two senses of “pilot” at work here. This episode is about my pilot study, the digital storytelling project in a faith-adjacent camp setting that I gloss as briefly as I could in Act 2 of Chapter 3. You can read more about that pilot project in this write-up I presented at REA 2018—and I hope later in a revised version of this article. If our family hadn’t decided to relocate coasts that same summer, St. Sebastian’s might have gone on to serve as the site for my main study as well.

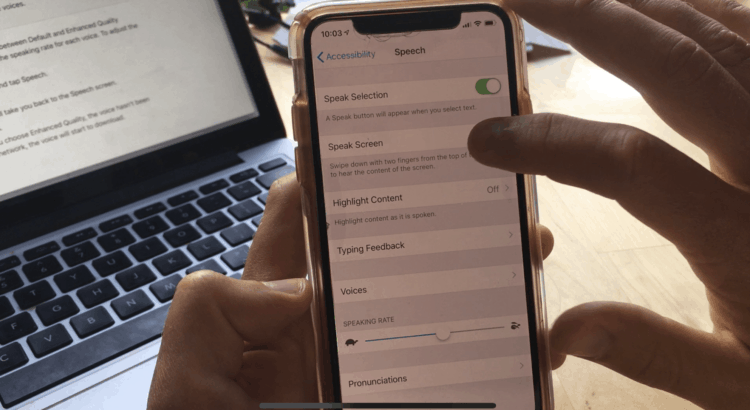

And then there’s the way that this pilot helped me try out some affordances of podcasting as research documentation, even though I significantly adapted the trajectory upon which I thought I was embarking.

So if you have a listen, I think there will be much that is familiar to you if you’ve been following Becoming Tapestry:

- a “cold open” segment to begin the show in the middle of the action;

- the use of pseudonyms to offer some protection of the identities of the participants;

- reflection in the midst of the narration on this novel way of conducting and presenting research;

- the theme music (“Intimate Moment” by MFYM);

- the structuring of the episode around a significant narrative and analytic turning point in the research project itself; and

- most importantly, the voices of young people reflecting on their experience of community and self-exploration within the site of the partner organization.

… strange

On the other hand, there are two things that are very different about this episode.

The first is the length. The episode clocks in around 13 minutes, which is comparable to the length of a single act in the format I eventually settled on.

I originally imagined that I’d be “podcasting through” the project, producing and releasing episodes along the way rather than when I had reached some discrete “end point.”

In that approach, I think shorter episodes organized around a single moment would have made sense. They would have needed to be much easier produce to turn them around quickly.

And it was the benefit of hindsight that made possible the longer narrative arcs of the episodes in what became Becoming Tapestry. I had to actually traverse multiple significant moments, and also have the perspective to select and weave in a couple significant pieces of existing literature, in order to tell a story that answered one of my research questions in a treatment that could feel complete, though of course not exhaustive.

Still, the trend in podcasting writ large has been toward shorter, more digestible episodes—audio you can listen to completely in an average-length commute. Like many scholars, I have a tendency toward unchecked verbosity, so I enjoyed and benefitted from being forced to be so concise. It’s fun to think about how the show might have taken shape according to this more condensed episode format.

The other big difference is in the tone of the tape. I love hearing the sounds of camp in the background of our conversation about what camp means. It’s such an improvement in terms of both illustration (“here’s what St. Sebastian’s Camp is like”) and intimacy (“here’s how we authentically related there”) over session recorded via Zoom.

Don’t get me wrong, I enjoyed reflecting a bit on how Zoe’s and her mentors’ home lives came to the fore as we recorded our conversations online. But I would have loved to “show” you Tapestry through field recordings not orchestrated from my apartment.

Take on a “Take 1”

Anyway, in the same way that I lauded the requirement of a pilot study in my Chapter 3 narration, I’d like here to laud the opportunity of a pilot “text” for those considering research documentation formats outside the usual “book chapter and/or journal article” academic box.

Not only did I benefit from the opportunity to experiment with form. I was also incredibly encouraged by the reception this pilot received at the 2019 Ethnography in Education Forum at the University of Pennsylvania.

Non-traditional research takes so long partly because you don’t have super relevant exemplars to follow. You have to be your own exemplar. So producing something you can share with others, get some feedback about, and gain some confidence from, is I think even more important than with more traditional kinds of projects.

So I hope you enjoy this pilot of a series that never came to be, but that gave birth to something different and perhaps better. More than maybe any other piece of media in the whole project, I certainly enjoyed making it.