![St. Thomas Aquinas. By Sandro Botticelli.Aquinat at de.wikipedia [Public domain], from Wikimedia Commons. St. Thomas Aquinas. By Sandro Botticelli.Aquinat at de.wikipedia [Public domain], from Wikimedia Commons](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/c/cc/Aquinat.jpg) “On the contrary …” the worldview that began to emerge with the rise of disciplined scientific thinking was fairly hostile to the idea of God’s action in the world. At the heart of this worldview was an awareness of mechanisms, the increasingly complex machines that began to emerge during this period with the help of scientific methods for understanding their operation. To return again to our image of the watchmaker, thinkers in the Age of Enlightenment began to wonder if the whole world might be understood via this metaphor. The plausible role of God was thus reduced to, at most, winding the clock at the beginning of time.

“On the contrary …” the worldview that began to emerge with the rise of disciplined scientific thinking was fairly hostile to the idea of God’s action in the world. At the heart of this worldview was an awareness of mechanisms, the increasingly complex machines that began to emerge during this period with the help of scientific methods for understanding their operation. To return again to our image of the watchmaker, thinkers in the Age of Enlightenment began to wonder if the whole world might be understood via this metaphor. The plausible role of God was thus reduced to, at most, winding the clock at the beginning of time.

The emergence of mechanics

To begin, have a look at this video. You don’t have to watch the whole thing if you’re not so inclined, but check out enough of it to get the general gist.

You probably know that this fabulous contraption is called a Rube Goldberg machine. The idea is to accomplish some task, usually a humorously trivial one, in as many steps as possible. Rube Goldberg machines make for great high school physics projects, because they allow you to bring together an arbitrary number of physical principles in the form of components in the overall machine. For instance, if you’ve been teaching your students projectile motion, then you could include in the assignment a component that requires the designer to successfully identify where such a projectile will land. Guess wrong, and the machine won’t complete its task.

What happened during the early modern period is that scientists got really good at guessing. Actually, it would be more accurate to say that they showed you don’t need to guess. If you know the right mathematics (in the case of projectiles, the shape of a parabola), you can simply calculate the answer. Beginning with Galileo, the branch of physics that has come to be known as mechanics has mathematically described, among other things, the movement of bodies subject to physical forces. One of the most relevant forces to the behavior of the universe is gravity, which Isaac Newton made great strides in describing:

With the work of Kepler, Galileo, and Newton, something quite extraordinary had been accomplished. Human beings could now reliably predict–calculate!–the movement of celestial bodies in the solar system and, in more and more cases, the movement of terrestrial bodies in the Earth’s atmosphere. Of course, some problems were harder than others. Wind resistance, frictional forces, and other complicating factors disrupt the ideal behavior described by the growing set of equations used to “model” the real world.

Perhaps it shouldn’t surprise us to learn that, amid this era of discovery, some physicists thought the science of mechanics could be the ultimate source of all explanation. Perhaps the entire universe could be reduced to mechanism. Perhaps the world is God’s endlessly complex Rube Goldberg machine, albeit one that carries out innumerable tasks in frightfully subtle ways.

Determinism, deism, and the “god of the gaps”

We turn for a simple statement of this idea, which is known as causal determinism, to Pierre-Simon Laplace. Laplace speculated that the techniques of mathematical physics could, in theory, be a sufficient explanation for both history and the future:

We ought then to regard the present state of the universe as the effect of its anterior [past] state and as the cause of the one which is to follow. Given for one instant an intelligence which could comprehend all the forces by which nature is animated and the respective situation of the beings who compose it–an intelligent sufficiently vast to submit these data to analysis–it would embrace in the same formula the movements of the greatest bodies of the universe and those of the lightest atom; for it, nothing would be uncertain and the future, as the past, would be present to its eyes. The human mind offers, in the perfection which it has been able to give astronomy, a feeble idea of this intelligence. [1, 4]

Can you guess where he’s going? Carl Hoefer writes, “Laplace probably had God in mind as the powerful intelligence to whose gaze the whole future is open.”

These ideas set in motion, as it were, a line of thinking that ends up relegating God’s role to, at most, setting what a mathematical physicist like Laplace would call the “initial conditions” of the universe. Once the initial state of the universe at t=0 is set, the mechanism can be set in motion to play out the predetermined drama of existence. God has infinite “computing power” and so can know what is going to happen. But God is also hands-off, taking the role of, in Polkinghorne’s words, an “Absentee Landlord” [2, 5].

This position is known as deism, and it exhibits an approach generally known as “god of the gaps.” This god doesn’t fare to well in the final analysis. Guy Consolmagno, summarizing the work of Michael Buckley [3], suggests that

the atheism of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries arose precisely because the religious thinkers of those times tried to base their religion on the new certainties of Newton and Leibniz. In some cases, they tried to fit the traditional ideas of an omnipotent, active God into the gaps where the new physics was not yet successful in completely describing how the universe worked … But as physics and chemistry developed, they kept reducing the role of God in the universe until he was nothing more than the clock maker who started things going and then watched them evolve from a distance. Finally, it reached the point where a mathematician like Laplace could quite properly say of such a God, “I have no need of that hypothesis.” [4, 41]

In the words of Douglas Adams, and in the minds of so many scientific skeptics, “Well That About Wraps It Up for God.”

The “causal joint” problem

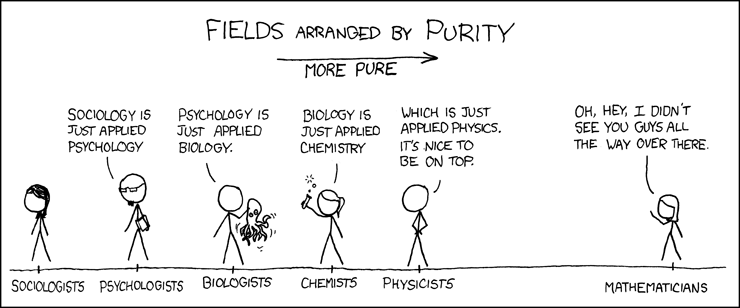

The crux of the challenge posed to theism by the mechanical worldview is what philosophers and theologians call the causal joint problem. Scientific skeptics purport to explain cause and effect through what Dawkins calls “hierarchical reductionism.” In this approach, physical mechanisms explain physical phenomena, chemical mechanisms explain chemical phenomena, biological mechanisms explain biological phenomena, etc. [5, 13; see also “Purity” comic below].

In such a view, there seems to be no “room” for God, no mechanism by which God can physically interact with the world, no joint by which God’s action can be linked in to physical mechanisms. The universe, it seems, is a “Closed Causal Web” [6, 263]. Of course, as Markham points out, “the classical concept of God” is not ignorant of the problems such thinking poses for the ideas of human free will and God’s control of natural phenomena. But Markham also notes that “most [modern] theologians find … very unsatisfying” the various ideas thinkers have put forth to address those problems [7, 4]. Plus, the reductionists dismiss such answers as so much impotent philosophizing in the face of concrete reality.

To summarize, then: It seemed, from a scientific perspective, that we were stuck with either (1) an increasingly impotent “god of the gaps” who does not act in the world at all or (2) a micromanaging Rube Goldberg God who knows everything that will ever happen and may also have ordained it that way. The former god becomes remarkably easy to dismiss altogether, and the latter God seems, to many thinkers, to eliminate the possibility of human freedom.

However, the bizarre and wonderful findings of twentieth-century science may once again have opened the door for speculation about plausible causal joints. We think these discoveries may clear the way once again for staunchly science-minded people to envision a God who genuinely responds to what happens in the world. The story will be the final of our course and also, we think, a fitting example of where the disciplines of science and theology can work together side-by-side in their quest for truth.