A sermon for the First Sunday of Christmas (Isaiah 61:10-62:3; Psalm 147; Galatians 3:23-25 & 4:4-7; John 1 :1-18)

Our Christian Feast of the Incarnation is twelve days long. So no matter how things fall in the December calendar, we always have at least one Sunday in this short liturgical season.

And that means we will always hear those majestic verses from the prologue of John’s gospel. The lectionary asks us every year to make sense of John 1 as a kind of nativity story.

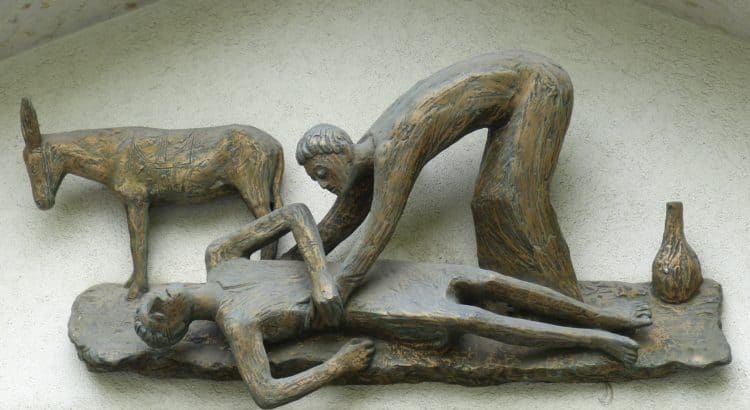

It’s a funny pairing: On the first day of Christmas, “shepherds keeping watch over their flock by night … go with haste and find Mary and Joseph, and the child lying in the manger.” And then on the first Sunday of Christmas, “the Word becomes flesh and dwells among us.” Same message, very different style.

Luke’s Christmas story is full of charming, down-to-earth details. There’s plenty that we can easily get our heads around in his account, even if we don’t keep livestock. The challenge is for us to remember that many of those details derive from the political context of empire and the disadvantaged social positioning of the Holy Family.

Still I’m usually up to that challenge much more enthusiastically. It’s strange to be celebrating the birth of a baby, a tiny human, with such mystic and even cosmic poetry and theology as we’ve heard this morning.

John 1 tells us the Word came to dwell in “the [very] world that had come into being through him.” God becomes part of God’s creation. And probably we need this sense of the cosmic stakes and connections, because by verse twelve the prelude is already telling us that this Word “who is close to the Father’s heart” has come to make God known to us, and still more audaciously to “g[i]ve [us] power to become children of God.”

It’s worth accepting the challenge to reckon in some way with John’s prologue in the midst of our dazed holiday fatigue. John needs us to know that there is a connection between the baby in the manger and the creation of the universe, between a human infant’s frail vulnerability and our startling capacity to become God’s friends and co-creators.

Jesus was born to show us God. Or is it better to say “to show us God’s love”? Is there any difference in those two ways of putting it? And if the Word was with God and was God and is the one through whom all things come into being, how do we understand whatever or whoever else was there in the beginning?

We can derive plenty of intellectual benefit for our faith by putting this and other passages under the microscope, studying the Greek, studying the philosophy of the day, studying what sense the church has made of all this since. That would be a good response on any given Sunday.

But our celebration of God’s Incarnation at Christmas is an especially sensory feast, with a baby at the center, getting glamorous and pungent presents and probably crying a bit more than the hymns would have us believe. So let me make a different suggestion.

If we want to experience John’s prologue and its proclamation in a more accessible and embodied and maybe Christmasy way, we might consider the metaphor that means so much to us here at St. Gregory’s.

I’m sure someone had remarked from this seat that when one looks up at Jesus on the Cross, one also sees him directly behind as the leader of the dance of saints. What if we see him in similar fashion behind the manger as we read from John 1:

In the beginning was the Word: the Word danced with God and the Word and the Dance were God. God danced in the beginning. Through the Dance all things came into being, invited to join another circle, invited to get in formation.

The Dance brought form and movement to the world, showed creation how to participate and also how to resist. But no wallflower could bring the Dance to a halt.

You get the idea. In Christ, the Word stepped aside from the transcendent but exclusive choreography of eternity and into the studio or the club where we enthusiastic amateurs mostly pull hamstrings and embarrass ourselves.

Jesus enters the created circle and teaches us, reminds us, of the beauty and simplicity of the Dance.

He shows us it is no less sacred if we sometimes step behind the beat or on our partner’s toes or even unexpectedly in a pile of manure. Even a baby can join the circle strapped to mom or dad’s torso, which, by the way, is how I invite you to look at the next Madonna and Child icon you encounter.

So, if you’re feeling lost in the cosmos upon hearing today’s peculiar Christmas gospel, it might be that the most faithful words from and to the preacher are something like, “shut up and dance.”

Merry Christmas: The Word has been made flesh and dances among us.

Image: “Andes Virgin & Child” by Artemio Coanqui via Enchanted Booklet (CC BY SA 2.0)