This post is part of a series wherein I blog my way through studying for the doctoral certification exam in the Communication, Media, and Learning Technologies Design Program at Teachers College, Columbia University. Read the first post here.

Full disclosure: Amazon links in this post have my affiliate code built into them. If you follow one and purchase something, I’ll get a small commission. Thanks for supporting Learning, Faith & Media and my other work.

As the test gets closer, I need to pick up the pace a little bit. Today I’m going to do an annotated bibliography-type post citing a bunch of literature and a brief takeaway about how it contributes to a question I haven’t really tackled head-on yet:

Why is digital storytelling an appropriate activity for faith learning ( / religious education / spiritual growth)?

OK, let’s get to it:

Putnam, R. D. (2000). Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster.

I cannot believe no one made me read this book in seminary. Religious leaders tend to talk about congregational decline as if it were the result purely of our insufficient faith / love of—for Christians—Jesus (unhelpful, frequently a tool for blaming progressives, plus an overly optimistic reading of what resulted in prior institutional thriving), the laziness that resulted from our prior institutional privilege (probably a piece of the picture in certain mainline denominations), and a failure to adapt ministry models beyond what worked in the 1950s-1970s (diddo).

But the piece we do not emphasize nearly nearly enough is this: Faith communities are not alone. Social participation and capital were on a steady decline across virtually every sector of American life for much of the second half of the twentieth century.

This doesn’t mean religious leaders should wash our hands, declare “it’s not about us” and give up on the idea that spiritual community will be important to Americans in the future. It does mean that congregational declines aren’t just about us.

The takeaway: Congregational decline should be understood against the backdrop of decline in social participation generally, including the fact that it is likely to continue. The causes Putnam identifies for diminishing social capital generally—generational succession, “privatizing of leisure time,” suburbanization, and financial pressure (p. 283-286)—should be instructive for congregational leaders in identifying new ministry models.

More the point, traditional models of congregational religious education like Sunday school are likely to be less and less tenable as a means of supporting the spiritual formation of U.S. adults and children in the future.

Drescher, E. (2016). Choosing our religion: The spiritual lives of America’s Nones. New York: Oxford University Press.

Drescher’s ethnography of “Nones” (those who do not claim a particular religious affiliation) is probably the most important recent work for helping us imagine the future (and present) of spiritual practice in the U.S. Among the important conclusions in the book are the following:

(1) Nones are a demographic category, not a demographic group. All that they have in common is answering a particular question in the negative, but not being members of particular groups doesn’t tell us much that is helpful overall about people in the category.

The upshot of all of this is that Drescher seriously challenges monolithic popular portrayals of Nones as young, white, wealthy, self-absorbed, etc. Her portraits attempt to treat Nones as individuals, to capture their diversity, and …

(2) … to push back on the extremely condescending way Nones are described and treated by many academics and many religious leaders. She writes of Nones’ “extra-institutional spirituality” and “self-authorized mode[s] of meaning making” in explicit contradistinction to prevailing terminology for their approach to faith: “narcissistic, non-committal, largely therapeutic” (p. 275).

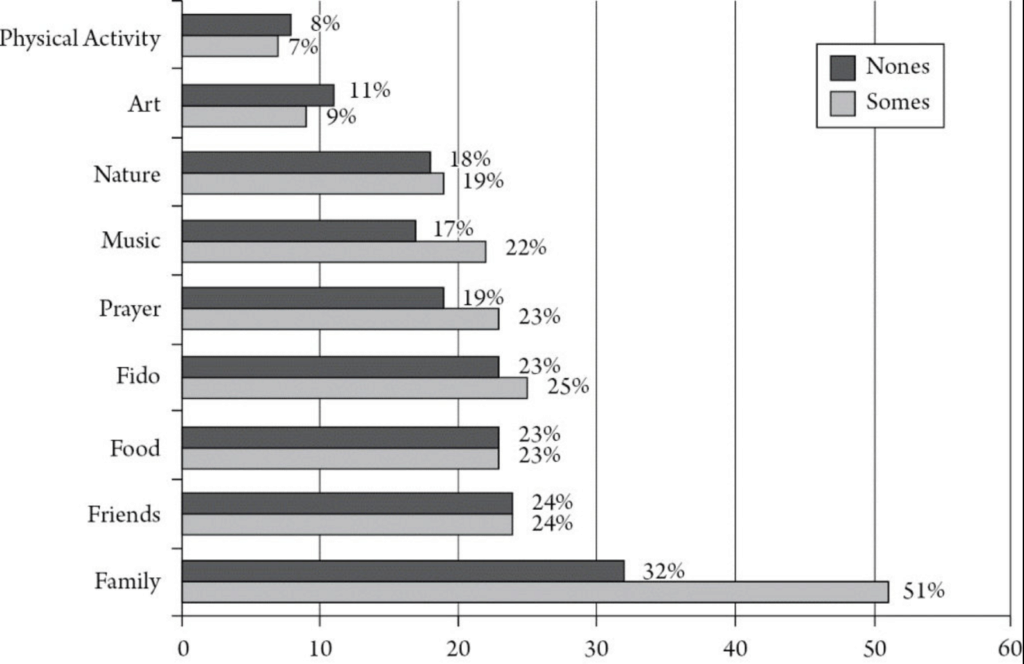

And she pulls back the curtain on just how similar many Nones are to many “Somes,” the latter being her term for the religiously affiliated, which term emphasizes spiritual and religious practice are spectral rather than binary. It’s not All or None, in other words.

(3) The Nones who do talk explicitly about sites and subjects of spirituality or more generally about sources of meaning in their lives are very likely to name the “four Fs” (family, friends, food, and Fido):

(My all-time favorite digital story covers three of the four:)

But in her portrayal of Nones, I recognize my own habits of spiritual practice and the advice I give to the people under my spiritual care, or who just ask my advice:

Find practices that work for you. Find what helps you be centered and grounded. Find what helps you be joyful and generous. Find what gets you out of your own head and puts you in relationship with the people and places around you, and maybe also in something bigger.

A big theme of this book is that many are indeed finding—with gusto. As others from Diana Butler Bass to Mary Hess have been saying for years, the future of religious belonging is likely to have more to do with practices and values than beliefs and affiliations.

The takeaway: The “aha” moment for me was here:

the unaffiliated resist such herding [i.e., overgeneralized labeling] not only as a matter of demographic correctness but also as a matter of spiritual identity and practice. Embracing the very noneness of Nones is critical for those attempting to understand the spiritual lives of the unaffiliated and an important starting point for understanding how American religion and spirituality are changing in general. (p. 23)

Something I hadn’t fully articulated yet is that storywork, like so many of the other practices described in the book, is a mode of spirituality that embraces Nones’ noneness. It is non-affiliative, non-dogmatic, meaning-centered, self-authorized reflection on what matters and how our experiences change us. And methodologies like Lambert’s Digital Storytelling are explicitly communitarian to boot.

Campbell, H. A., & Garner, S. (2016). Networked theology: Negotiating faith in digital culture. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic.

Campbell, H. A. (2012). Understanding the Relationship between Religion Online and Offline in a Networked Society. Journal of the American Academy of Religion, 80(1), 64–93.

Probably the most prolific scholar of how the Internet is shaping religion, and sometimes vice versa, is Texas A&M communication scholar Heidi Campbell. What began with a really awesome digital religion lit review in 2012 and takes a more theological form in her 2016 book is a model of she calls networked religion. It’s characterized by five traits:

- networked community – religious community is exercised and experienced in part or in whole through networked publics

- storied identities – the Internet is a tool for assembling and integrating religious identity through agentive, narrative meaning-making

- shifting authority – “credentialed”/institutional religious leaders and the hierarchies they maintain are less likely to be blindly deferred to; the Internet provides opportunities for both traditional and emerging religious leaders to develop or consolidate authority through blogging, etc. (and wow does this have the theology police freaked out)

- convergent practice – digital tools/spaces/media give new and varied expression to timeless rituals and actions; “[t]he internet serves as a spiritual hub, allowing practitioners to select from a vast array of resources and experience in order to assemble and personalize their religious behavior and belief” (sound familiar?)

- multisite reality – digital spaces are generally integrated and connectional and act as a supplement to in-person practice rather than being separate and distinct and acting as replacements to in-person practice

The takeaway: The relationship between religious practices and digital practices is complex. Campbell’s work gives us concrete theoretical tools to name and better understand the empirical realities of religion online.

In particular, trends in the importance of personal story, the creativity with which people appropriate religious rituals and messages in/on new media, declining de-facto deference to what institutions and their leaders think is important, and the use of digital spaces as reflection sites for in-person experiences all speak to the potential of digital storytelling as modality of identity development and self-reflection with great potential to faith communities today and in the future.

As usually I’ve written more and covered less than I intended. Will do part 2 ASAP: Hess, Cheong, Hilberath & Scharer, McGuire, ??.

Kyle, this post was particularly clear and helpful to me in thinking about the Nones and how digital story tellling fits into faith formation. Your blog is fascinating. Thanks again, Suzanne

Glad to hear it, Suzanne. Thanks for reading!